Canary in the dopa-mine: the technology of addiction

Generating dependency at scale, for profit, is the oldest game in town

You aren’t lonely because of your phone. You aren’t unhappy because of social media. You have in your hand a collection of some of the most powerful tools humans have ever devised, and you probably aren’t addicted to them so much as you are defending yourself against a broken world with them.

Saying that the technology itself, the devices, the apps, are the root of the problem is the same distracted logic as a billionaire who says “kids these days” can’t afford a house because they buy too many lattes. When organized labor, pensions, and even minimum-wage jobs gave past generations the privilege, they then systematically and parasitically looted future generations of the same opportunities.

If you feel sad or alone or disconnected or disenfranchised or feel like you’re faking it 24/7, that’s because you are supposed to. That’s a feature of our economy, not a bug. That’s the design.

Yes: it’s still important to be conscious of how dependency-generating our devices are designed to be. And yes: the intersection of all these factors can contribute to a mental health spiral that is terrifyingly difficult to pull out of.

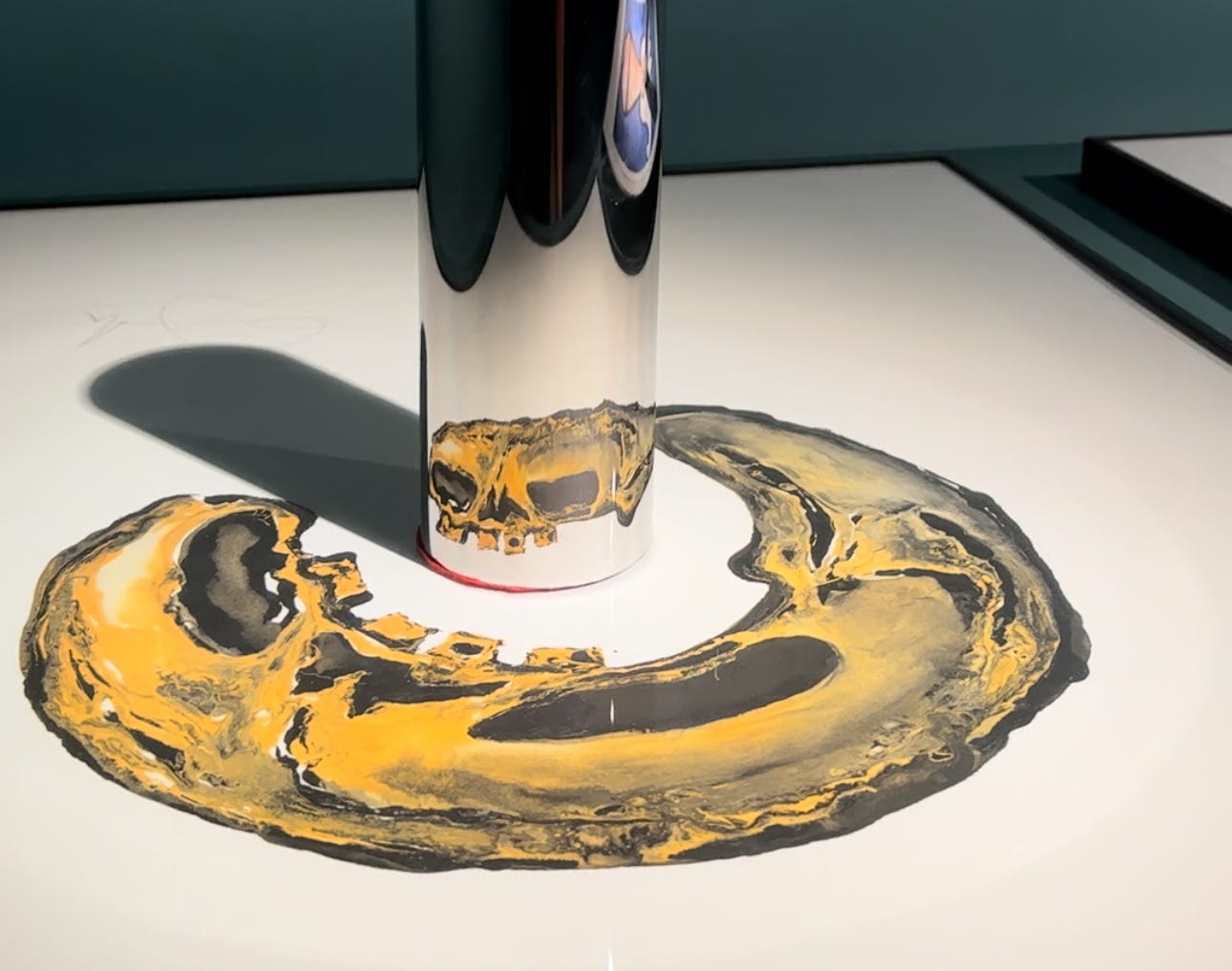

But blaming the phone, or the app, or the AI, is to forget a fundamental fact about technology: that it is a long lever on the world, for anyone and everyone willing to use it. And it is being used against you, at every opportunity, for profit. But technology is the lever, not the man with his hand on the lever.

When a coping mechanism becomes a chain

Dependency is a challenging topic, individually as well as socially. It seems to touch on every nerve we have, from shame and guilt, to personal responsibility and public health. It informs and interweaves with every force in our nutritional, psychological, and spiritual lives. What does it mean to need a thing? What if that thing is also a tool? A lifeline? A window into your community?

Technology addiction’s amalgam of sociopolitical and deeply personal, somatic elements shares much in common with two other modern demons: substance abuse and obesity. It’s important to not link them too closely, but there are enough parallels here that it’s worth unpacking where and how they diverge.

These conversations can be roughly divided into two lanes: individualist, and systemic. Both are necessary and relevant. It’s temptingly easy to point to “the system,” to billionaires behaving badly, to the tendencies of empire, as reasons why this suffering endures within ourselves, our loved ones, our communities. They can sound like excuses.

We also tend to think we have more individual control than we actually do. Your consciousness can be described as an emergent property of the biological process occurring inside your brain. The decisions you make may not be quite so conscious as you believe them to be. Human memory and logic are deeply flawed. We are subject to hacking in predictable ways.

Ask anyone who practices stage magic: your attention can be caught, trapped, played with. Every one of your senses can be complicit in this. Distraction is an art form. Misdirection, mentalism, probability, sleight of hand. This is not to say that free will is an illusion, but you must concede that your meat-body possesses some level of control over your ability to access your idealized self.

In the systemic view, digital dependency is broadly similar to chemical dependency, though less overtly fatal. Both are many-headed craving monsters with wide avenues of research and a checkered history of public health initiatives. Or draw similarities to obesity: we can avoid fat-shaming while also acknowledging the shared links with poverty, education, and genetics. But on the individual level, telling someone with a brain tumor that someone else’s struggles with cocaine have some kind of equivalence, in terms of agency, can feel like a slap in the face. Brain cancer guy didn’t do this to himself! Drug addict guy definitely bears some responsibility for making himself a statistic, right? The solution is obviously to convince these people to turn their lives around!

Sure. Your actions have consequences. You’re still accountable for being who you are, eating what you eat, swiping who you swipe, even if it isn’t always a choice made in crystalline conscience.

Still, at the risk of sounding like a spineless fence-sitter, I am the person who constantly says things like, have you noticed how these “epidemics” never seem to be evenly distributed? The fact that we can correlate certain cancers and rates of substance abuse with geographies as granular as ZIP codes would indicate that neither are issues of pure autonomy. As for technology addiction, it turns out that you can find geographic, gender, and economic patterns in rates of problematic smartphone usage levels just as easily. If you’re a 25-year-old woman in Southeast Asia, with your entire social sphere embedded in a collectivist culture, the chances that you spend 8+ hours a day on your smartphone are perhaps not shockingly, quite high.

Can we make this about porn, though?

Let’s say you have an addictive relationship with some aspect of technology: Netflix binges, news-junkie doomscrolling, hours of TikTok in bed. Maybe your flavor of fixation is a single-malt online gambling habit. Maybe it’s a a spicy blend of several different avoidant avenues, dancing across the apps. Cocktail metaphors aside, at what point does your behavior qualify as self-harm? Do you have to identify as an addict to finally kick the craving?

Pornography has always, um, stood proudly as a historical example of mental hijacking. Sex sells. Thirst trap. Eye candy. But the difference between keeping a collection of naughty VHS tapes, versus the purified mainline potential of a free-for-all for eyeballs, cloud-enabled, instant-gratification, all-you-can-eat buffet at your fingertips has not and should not escape the notice of hard-working social welfare researchers.

Actually, that last article kind of spoils this whole narrative with one quote: “Despite all efforts, we are still unable to profile when engaging in this behavior becomes pathological.” Seems like determining a boundary beyond which your level of porn consumption could be defined as harmful, is about as challenging as defining what constitutes porn in the first place. Maybe clinicians just “know it when they see it”?

And if we can’t decide at what level a porn habit becomes disorder-worthy, we’re going to have a bad time attempting to make the same distinction for smartphone addiction.

Don’t hate the player, hate the game

There are plenty of very online people producing chirpy content telling you to own your shit. For what it’s worth, I agree with them, and that’s also not why I’m writing this. If any of this hits a little too close to home, then reading a blog about brain shit won’t be the first or last time you’ll feel confronted. Internalized stigmas about words like “addict” don’t help either, so it’s worth doing what you can to release them, whichever role you play in the consumption ecosystem — from content creator to therapist.

Awareness isn’t the same thing as a cure, but it can lead you to start asking the right questions. Nor is a luddite’s life, sans iPhone, morally or functionally superior. But when all the forces of consumer psychology arrayed against you begin to repeat their mantras — “productivity”, “intelligence”, “possibility” — while marketing the latest version of a little glass abyss that they’re spending billions getting you to stare into, remind yourself to stare into the consumption machine instead.